On my blog I mostly write about AI, indie tools, and the small apps I ship at night.

During the day, though, I still work in the in-vitro diagnostics (IVD) industry with Japanese companies that look at China carefully. Every week I keep a short private briefing log based on public reporting. This post is adapted from one of those notes.

Recently, Chinese and overseas media both covered a new wave of originator drugs withdrawing from the Chinese market. On social media the story was quickly simplified into a slogan: “imported drugs are leaving; domestic generics can’t be trusted”.

That narrative is emotionally understandable, but technically incomplete. Here are a few structured notes for non-Chinese readers trying to make sense of it.

A very rough primer on VBP

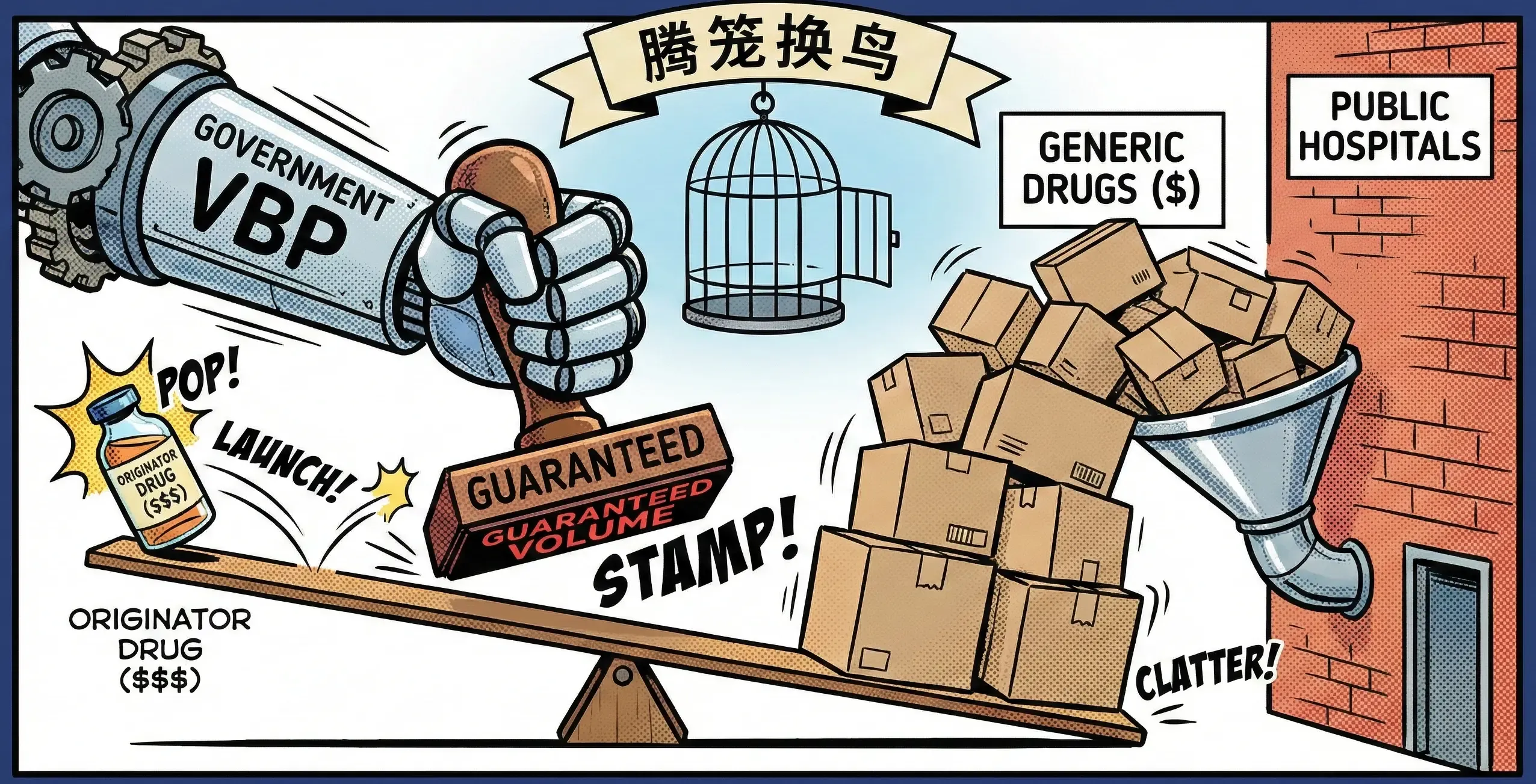

Since 2018, China has been rolling out volume-based procurement (VBP) schemes for drugs and devices. The rough idea:

- The government centrally tenders large volumes of essential medicines.

- Companies bid aggressively on price; winners receive guaranteed volume.

- In exchange, public hospitals are expected to switch to the winning products.

For off-patent originator drugs, this is brutal. Once cheaper generics pass quality consistency evaluation and win tenders, the originator often loses its reimbursement position in major public channels. Pricing freedom in the private channel is not enough to compensate for lost volume.

The policy slogan you sometimes hear is “腾笼换鸟” (teng long huan niao) — literally “empty the cage and swap birds”. In practice it means:

- Use cheaper, good-enough generics to save money in broad coverage.

- Reinvest the savings into reimbursing expensive innovative therapies faster.

From a macro-budget perspective this logic is coherent. From the standpoint of individual patients who suddenly cannot find their original brand drug, it is painful.

The headlines: imported drugs are “leaving”

Recent official notices show dozens of imported or joint-venture drugs voluntarily withdrawing their registrations. Some reports count more than 150 products over the last few years. Examples include well-known antidepressants and ADHD medications.

Regulators frame this as company-initiated cancellations rather than forced safety withdrawals. The economics are straightforward: under VBP and tighter pricing, many legacy originator products simply no longer make financial sense to maintain.

However, what patients experience is different:

- Hospital ordering systems stop listing their familiar imported brands.

- Pharmacies tell them that only domestic generics are available.

- Media and social media compress a complex policy into a simple impression: “even if I have money, I can’t buy the drug that works for me”.

That emotional gap matters more than any Excel sheet.

Why the trust gap is so wide

Several Chinese articles interviewed physicians who described everyday frustrations: antibiotics that do not seem to work as expected, anaesthetics needing higher doses, blood-pressure medications that feel weaker than originators.

These are anecdotal and not controlled trials, but they resonate with patients who already remember older scandals around substandard generics. Even if regulatory standards have improved significantly, trust moves slower than policy.

In theory, once generics pass bioequivalence and consistency evaluation, they should be interchangeable with originators. In practice:

- Tiny differences in formulation, excipients, and release profiles can matter for sensitive patients.

- Switching stable psychiatric or neurological patients to new drugs is never easy.

- Communication about why a switch is happening is often rushed or missing.

So the withdrawal of imported drugs does not happen in a vacuum; it lands on top of a long history of uneven quality and communication.

The macro logic: an impossible triangle

If we zoom out, China faces the same impossible triangle as every public health system:

- Quality — patients want safe, high-quality drugs and diagnostics.

- Access — broad coverage across a huge population.

- Cost — budgets are finite.

China’s current answer looks like this:

- Use VBP and generics to secure basic, widespread coverage at lower unit cost.

- Use the savings to rapidly list innovative, high-priced therapies in the national reimbursement list.

If you read the annual updates to reimbursement lists, you see expensive oncology and rare-disease drugs entering much faster than a decade ago. Those budgets come from somewhere; VBP is one of the key sources.

Seen this way, originator withdrawals are not simply “foreign companies fleeing” but part of a deliberate reallocation of limited resources.

What this might mean for Japanese and global companies

From my vantage point in a Japanese IVD company, a few observations:

- Off-patent originator products can no longer rely on brand and history alone. Competing after VBP means accepting commodity pricing or exiting.

- For diagnostics and devices, similar dynamics are emerging: bundled purchasing, local competition, and more scrutiny on cost-per-test.

- Companies that want to stay relevant in China will need either:

- Genuinely differentiated innovation that justifies inclusion as a reimbursed high-value option, or

- A willingness to play in the competitive, lean-cost generic / me-too space with local partners.

None of this is surprising at the strategy level, but it becomes vivid when you read individual patient stories in Chinese and English media.

Personal takeaway

This week’s news is not just a China story. Under different names and mechanisms, many health systems are quietly moving in a similar direction: more pressure on price and volume, less room for comfortable margins.

A few things stand out to me:

- The arithmetic is global. Ageing populations and chronic disease are pushing demand up everywhere, while public budgets grow slowly. Even in high‑income countries, payers are asking harder questions about what they get for each dollar.

- Capital is looking elsewhere. Major economies are clearly prioritising investment in AI and other high‑tech sectors. Healthcare and pharma remain important, but are being asked to deliver more value per unit of spend rather than simply “more”.

For patients, that often translates into more switches to generics, tighter formularies, and procurement schemes like VBP. For companies, it means the old formula of “high list price + slow erosion” is under real pressure.

I do not expect the cost‑effectiveness trend to reverse. The more interesting question is whether we can balance that pressure with transparent communication and enough innovation so that people still trust the medicines and diagnostics they rely on.