From a flu shot cheaper than Mixue milk tea to the real pressure on China’s vaccine industry

How China’s vaccine market is structured

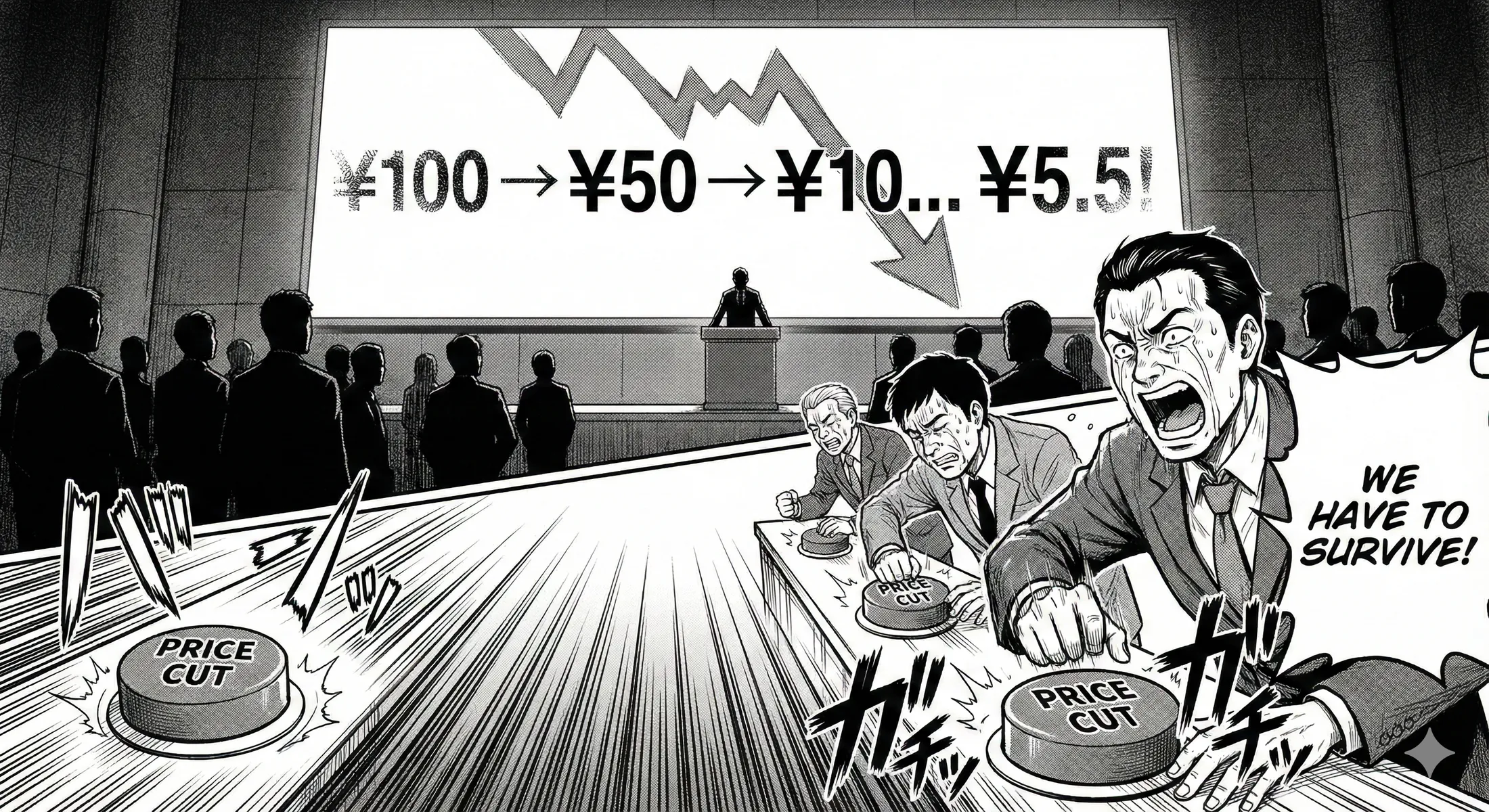

Over the past few days a long feature from Tencent News’ “Qianwang” column has been circulating widely. It dissects China’s vaccine price war, and the line everyone keeps screenshotting is simple: in Beijing, one company won a tender for a trivalent influenza vaccine at 5.5 yuan per dose, already cheaper than a cup of Mixue Bingcheng milk tea. Almost immediately, the China Vaccine Industry Association felt compelled to issue an open initiative “against involution-style competition”, explicitly banning bids below cost and threatening to warn, publicly criticise, or even expel violators. When an industry long described as high‑tech and heavily regulated has to rely on its own trade association to plead with companies to stop undercutting each other, it is a sign that the problem has moved beyond pricing tactics into structural imbalance.

Start with the basics. Regulators roughly divide vaccines in China into two categories. Category‑1 vaccines are procured and funded by the state and given to children under the national immunisation programme; margins were never high. Category‑2 vaccines depend on out‑of‑pocket payment and are where companies historically made real money: influenza, HPV, shingles, pneumococcal, rabies, and so on. Over the past few years, this lane was pushed forward by capital and storytelling: “rigid demand + high margin” sounded like the perfect narrative. The result is that for almost every mainstream product, you now see ten or more companies lining up to compete on the same indication. Pipelines are crowded, development paths are highly similar, and there is relatively little differentiated clinical value.

This is why, even though vaccines have not formally entered national‑level volume‑based procurement (VBP) the way many chemical drugs have, prices are still being driven down to the floor. Local central tenders and various “惠民工程” (people‑benefit programmes) function in practice very much like “exchanging price for volume”. Local governments want to contain healthcare spending, so they are happy to lock in budgets with the lowest possible bid; tender platforms rank offers by rule, which usually means lowest price wins; companies worry that once they lose a tender, production lines and promotion teams will sit idle, so they follow each other down through round after round of cuts. In that kind of environment, it is not hard to find a “spark” for collapse. It is rarely that a single policy suddenly rewrites the rules; it is that a market already overcrowded and undifferentiated is hit with a strong, sustained price‑oriented mechanism.

Blaming everything on tendering rules, however, is too easy. Imagine the market looked more like Europe or the US: a small number of oligopolistic players, highly concentrated products, and very high entry barriers. Even with central purchasing and large‑scale public procurement, prices would go down, but they would probably not be pushed to “cheaper than milk tea”. Western payers also worry about healthcare budgets, and public systems also negotiate hard on price, but you very rarely see a technically demanding vaccine being sold for the price of a subway ticket. The real difference lies in how fast and how broadly China expanded vaccine production capacity in this cycle, far beyond what demand could reasonably absorb.

Overcapacity and a crowded supply side

On the supply side the picture is straightforward. When Pfizer was the only supplier of the 13‑valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), people talked about “high technical barriers” and the profitability of multinational originators. A few years later, domestic manufacturers began to win approvals one after another, and more companies are still in the clinical queue, with a dozen or so PCV13 candidates in the pipeline. Influenza tells the same story: a handful of leading firms used to be able to supply the whole country, but new production lines, new processes, and new approvals kept coming; more than ten companies now produce rabies vaccines; even high‑margin HPV vaccines quickly went from “undersupplied” to straightforward price war—several hundred yuan per dose down to a few dozen, then another step down through “buy one get one free” and “buy two get one free” promotions that keep dragging the psychological price floor lower.

Demand, at this moment in the cycle, has not provided a strong enough cushion. “Vaccine hesitancy” now appears repeatedly in listed companies’ semi‑annual and annual reports; it is no longer a term you only see in Western public‑health debates, but something reflected in real uptake data. China’s influenza vaccination rate has long been low: the average coverage rate across the whole population is under 4 percent, nowhere near the roughly 50 percent seen in many Western countries. A deeper structural variable is demographics. Births have been falling, shrinking the natural market for traditional paediatric vaccines. Companies that used to focus on children have had to pivot collectively into adult Category‑2 vaccines—flu for the elderly, HPV for adults, shingles for older age groups—turning the adult vaccine lane into another packed red ocean.

Against this backdrop of supply–demand mismatch, central tenders and 惠民工程 programmes are more like amplifiers that bring the problem to the surface faster and more sharply. From a public‑health perspective, it is good policy when local governments fund free flu shots for seniors or free HPV vaccination for schoolgirls. Coverage rises, disease burden falls, and society as a whole gains. But if the purchasing side is defined by two hard constraints—limited budgets and a strong bias toward low prices—and the supply side consists of a dozen highly similar companies chasing the same product, then low price stops being a strategic choice and becomes a survival game you are dragged into. Industry associations can issue initiatives and call on members to avoid bidding below cost, but once the fear of “whoever stops first dies first” dominates, paper‑based self‑discipline is hard to sustain.

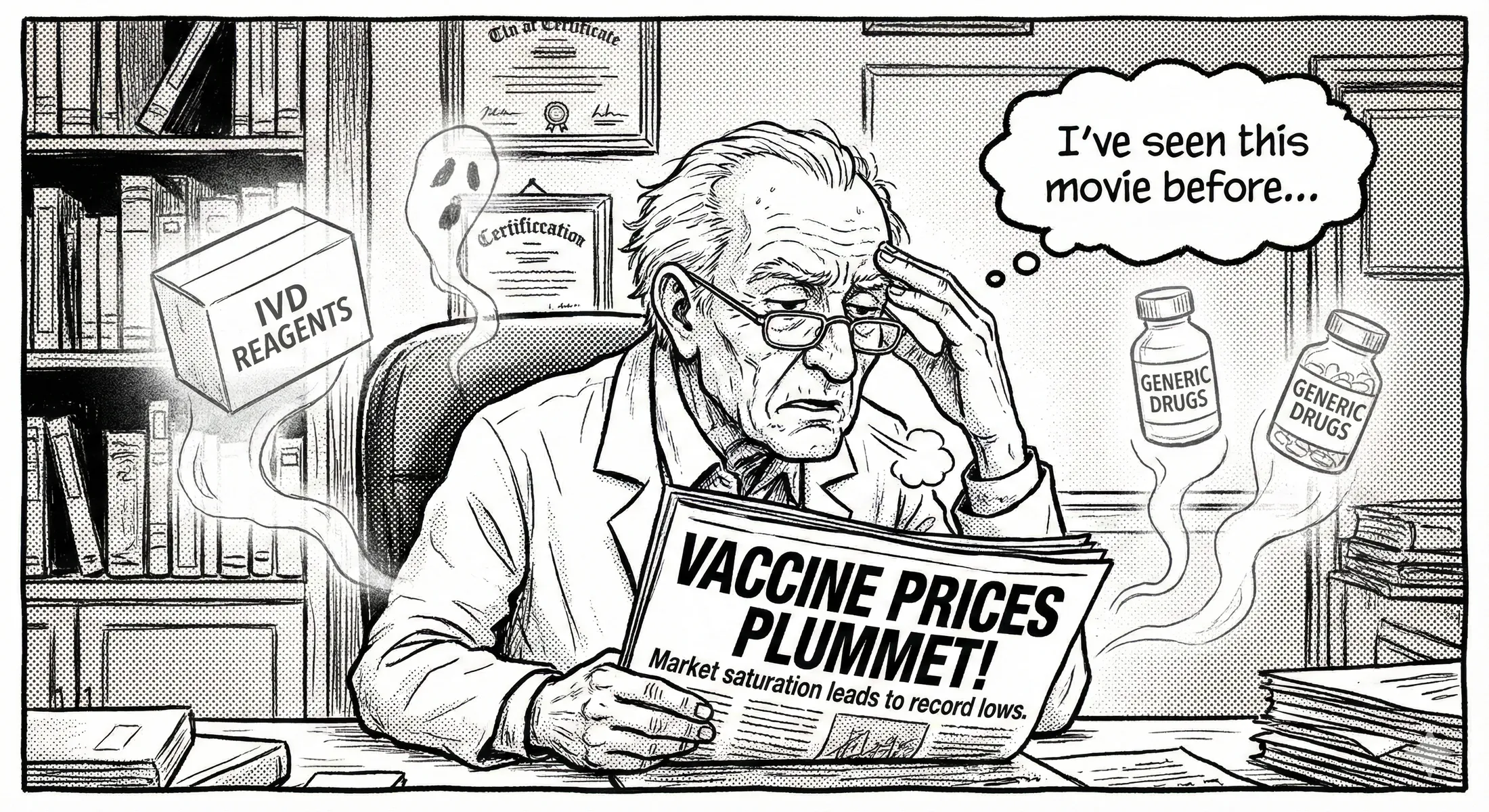

That is why vaccines reveal something broader than “whether a product is in VBP” or “whether the insurance system is squeezing margins”. In recent years, prices for in‑vitro diagnostic (IVD) reagents and generic chemical drugs have been cut again and again, and public commentary often settles on the same explanation: the state is rolling out VBP, insurers are trying to control costs, and companies are being squeezed. The vaccine story is a reminder that the true floor for prices is usually not set by the name of a policy, but by how homogeneous the products have become and how far capacity has overshot real demand. When you see a dozen companies and dozens of production lines in a single category, all making essentially the same product for a limited—and sometimes shrinking—market, prices will eventually collapse. The only unknown is which tender round triggers the drop.

Lessons beyond vaccines: IVD and generics

IVD is a textbook “hidden copy” of the vaccine story. Many test kits and diagnostic consumables are technologically mature; regulatory paths are clear; the barriers to entry are nowhere near what they were fifteen years ago. So you end up with a large group of companies all taking similar products to the same hospitals and the same budgets, competing through relationships, field sales, and channels, and when there is nowhere left to retreat, through price. Drugs follow the same pattern. After a wave of patent expiries and rapid generic launches, if everyone is making the same generation, the same strength, and the same formulation of a “standard” product, then regardless of whether VBP is formally involved, the endgame looks similar: a slow, grinding decline in margins, followed by a round of concentrated purchasing or VBP‑style negotiations that drive prices decisively below psychological thresholds.

Strategic choices for multinationals

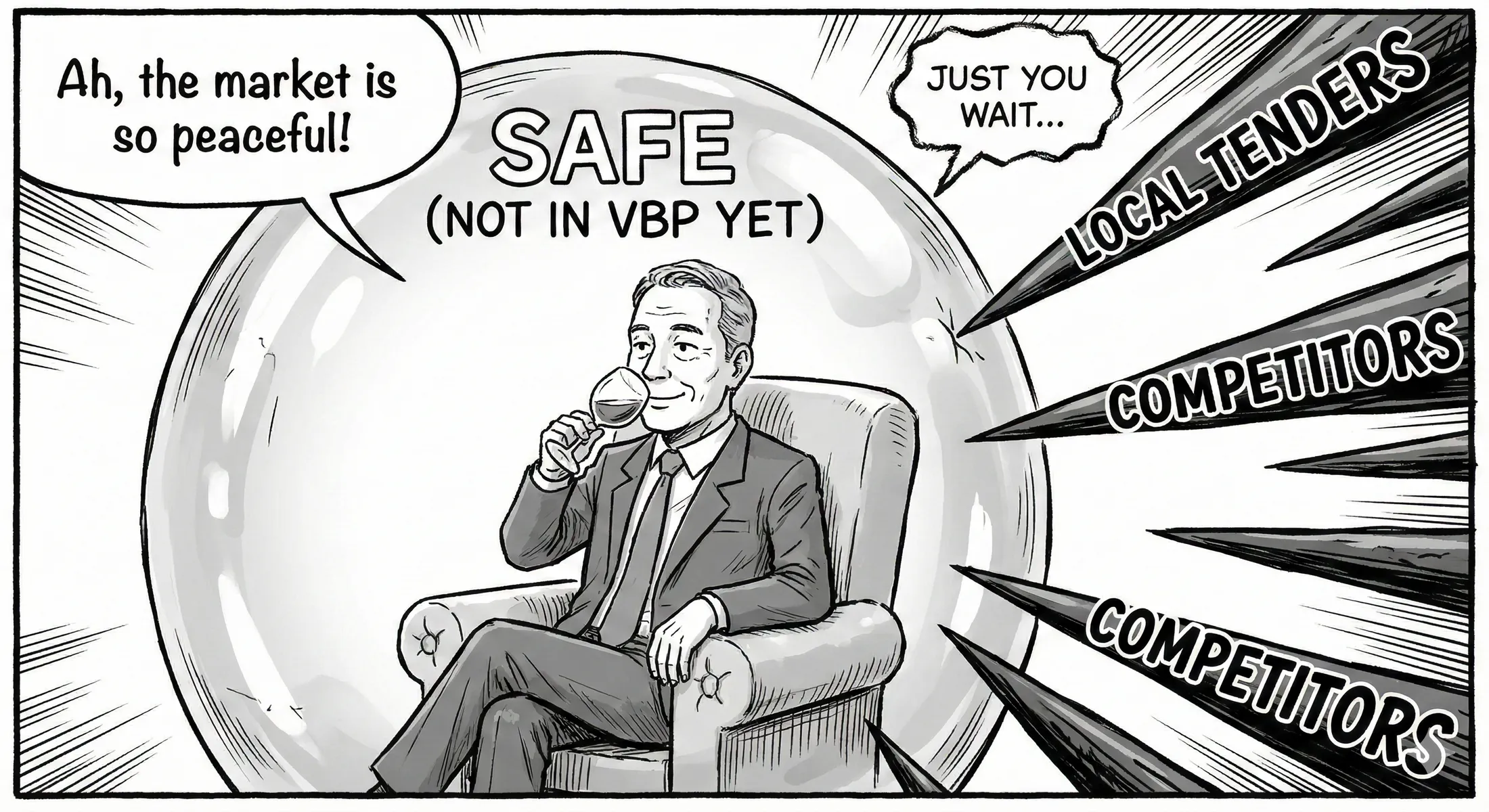

For multinational companies that still view China as a growth engine, the vaccine episode is a very direct reminder: you cannot build a China strategy by staring only at the line that says “in VBP or not”. In internal discussions over the past few years, many pharma multinationals have put “VBP risk” at the top of their China slide decks and tried to avoid it by choosing products unlikely to enter the programme or by steering clear of certain reimbursement negotiations. But if you look closely at vaccines and diagnostics, you see that this “bypass VBP” logic only addresses one institutional variable. It does not touch the core question: are you trying to do genuine differentiation, or are you signing up for hard‑fought commodity competition?

Choosing differentiation means accepting more uncertainty on the product side: tougher targets, less proven technologies, segments with genuinely unmet clinical needs, the costs of early market education and promotion. The upside is that if a product works, it is harder to drag into a cabbage‑price battlefield. Even when generics and followers appear later, you have something to defend—technical advantages, brand, or robust clinical evidence. Choosing competition means accepting that you are in a fully marketised lane, and that you will fight on highly homogeneous products using cost control, manufacturing efficiency, local operations, and deep channels to go head‑to‑head with domestic players. It is a bitter path and leaves little room for the old assumption that “multinationals naturally earn high margins”, but at least it is honest.

The truly dangerous state is the third one: telling yourself that “as long as we stay out of VBP, prices will hold up”, while in reality operating in a category that is already crowded and extremely sensitive to price signals, with no real differentiation and no structural cost advantage, relying only on brand inertia and first‑mover legacy. In that condition, market turning points tend to arrive suddenly. A minor tweak in tender rules, the expansion of a local惠民工程 programme, or a few domestic players collectively undercutting the field can turn what once looked like a stable cash flow into a sharp line of impairments and losses on the P&L.

In that sense, the 5.5‑yuan flu shot that is cheaper than Mixue milk tea is both the extreme end point of the vaccine industry’s own trajectory and a mirror for the broader Chinese pharma and diagnostics sector. Over‑optimistic narratives, over‑rapid capacity expansion, overcrowded pipelines, and an over‑reliance on policy tailwinds and local projects have pushed many businesses that could have made steady money for a long time into a corner where they can only fight with price. Anyone who still wants to treat China as a key market in this environment has to answer a more uncomfortable question than before: are you here for the illusion of a world without VBP, or for something that is genuinely hard to replace?