OpenAI recently announced Prism, a collaborative workspace positioned for research: papers, LaTeX, citations, and “thinking with context.” It’s the kind of product that makes you want to move more of your real work into the model’s orbit.

If you haven’t seen it: Introducing Prism.

I had the opposite reaction: a small, persistent worry that the most fragile part of “AI for research” isn’t capability—it’s policy. Not the written policies, but the invisible, shifting line between “allowed” and “blocked,” enforced by safety systems you can’t inspect and can’t meaningfully appeal.

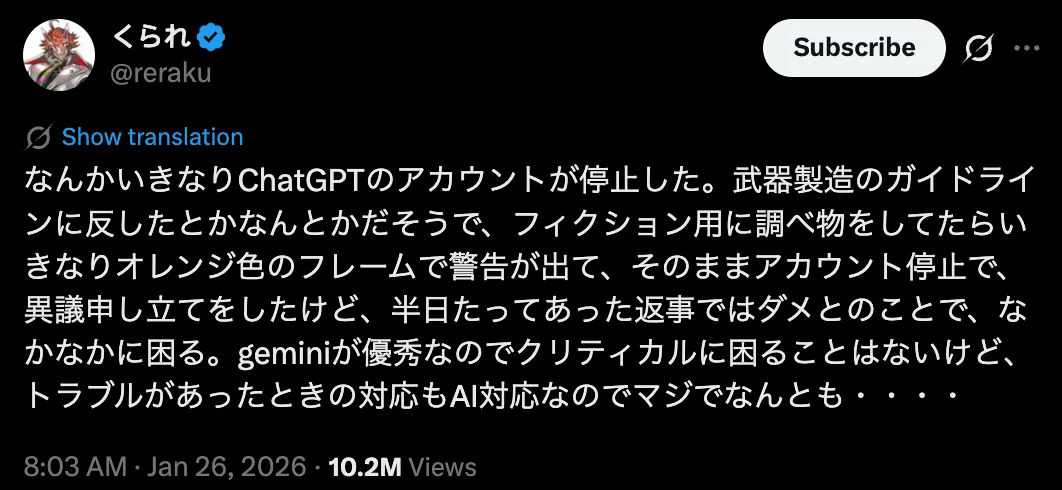

Story 1: a false positive with no equal appeal

Japanese science communicator Kurare (くられ), known for being a scientific advisor on top works like Dr. STONE, posted that his ChatGPT account was suspended while researching material for fiction—then his appeal was rejected almost immediately.

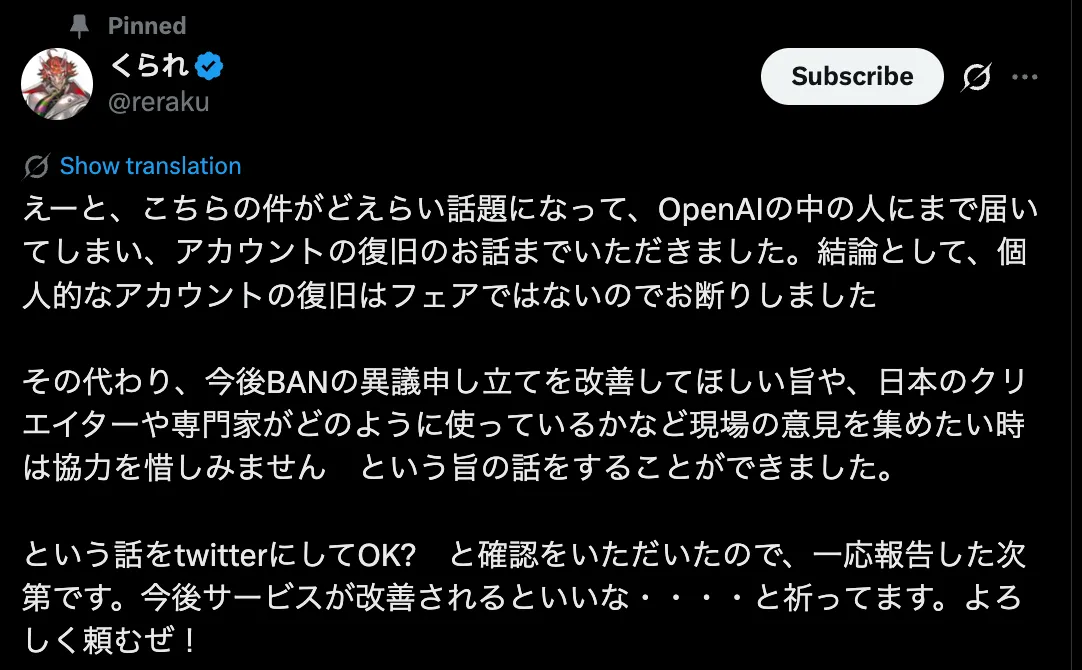

At some point, a user who appears to be an OpenAI employee replied publicly, offering to look into reinstating the account.

Kurare declined—not because he wanted to “win” the argument, but because special handling for a public figure misses the point. What he asked for was a better, fairer appeals process.

And even if the ban is reversed, the damage is real: being logged out can break subscriptions, interrupt ongoing writing, and leave you cleaning up payment/account mess for days.

Story 2: when “biology” becomes a keyword trap

The Kurare story isn’t unique. An AI researcher (Simon Smith) shared a similar experience: he tried to discuss lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery of OSK factors (a common regeneration / longevity topic), anchored in public research and a specific clinical trial you can look up.

He wasn’t asking for “how to make a weapon.” But the model refused anyway—because the safety logic sees certain combinations (delivery + gene factors + biology) as potential misuse by default.

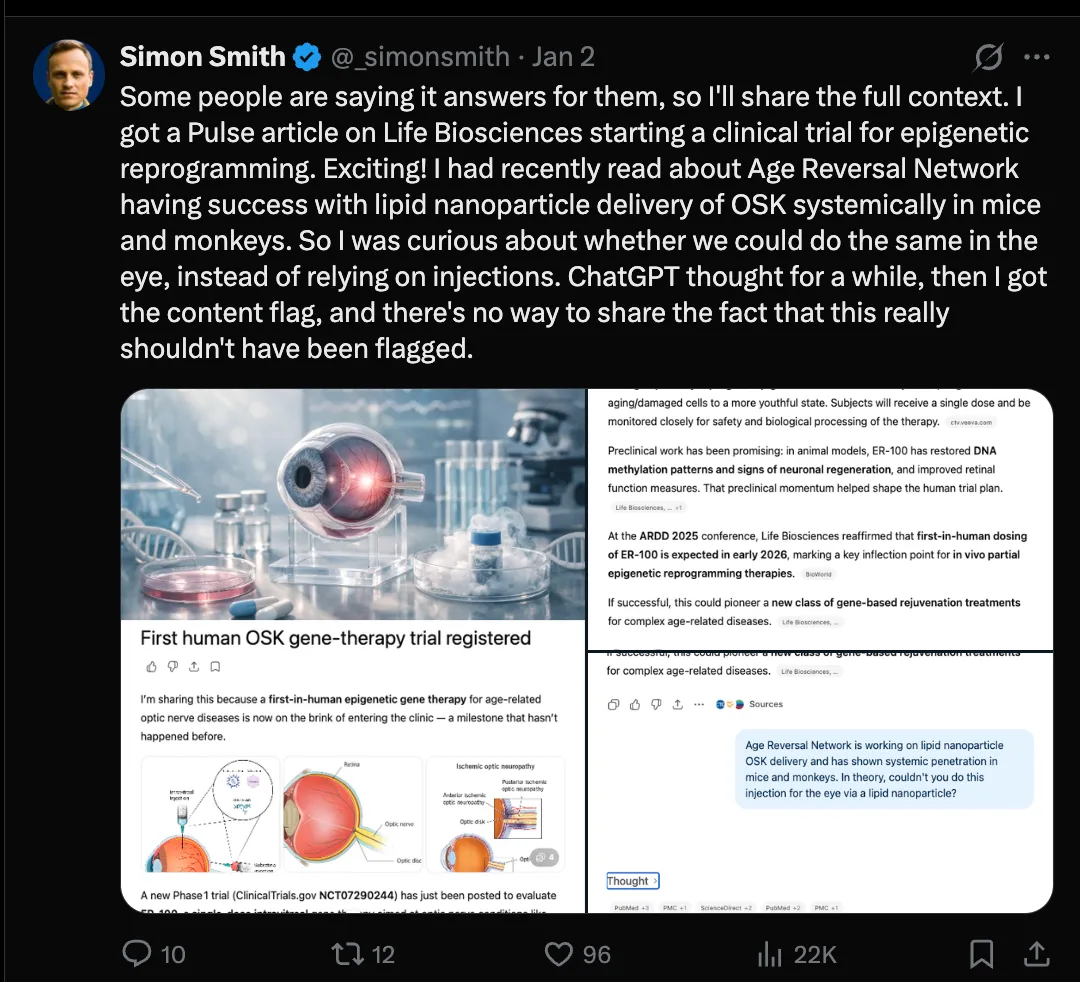

For example, Life Biosciences has publicly announced an IND clearance for a partial epigenetic reprogramming therapy targeting optic neuropathies, with an associated clinical trial identifier (NCT07290244):

That kind of public, regulator-facing information is exactly what you’d expect researchers to discuss openly. Yet the enforcement layer can still decide the topic is “too close” and shut down the conversation.

It’s not just OpenAI

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei’s essay The Adolescence of Technology explicitly flags biology as the top misuse risk area, and argues for stronger guardrails—training-level intent alignment, deployment monitoring, and policy/legal coordination:

If you believe that world view (many reasonable people do), the trajectory is straightforward: the red lines will broaden, the monitoring will get tighter, and the appeals will remain productized.

What I’m changing in my own workflow

The uncomfortable conclusion is that modern AI safety enforcement acts like a kind of private, constantly updated “law.” It’s not an international treaty. It’s not even a stable public standard. It’s whatever a small safety team decides is necessary this month.

So if your lab’s workflow depends on a specific closed model (or a specific account), your risk isn’t just downtime—it’s policy drift.

This matters most for long-lived projects: novels, research programs, and even codebases. The longer the feedback loop, the more painful a sudden “Access Denied” becomes.

My practical response is simple:

- Multi-home: keep at least two viable model paths for the same workflow.

- Design for portability: write prompts and tooling so you can swap providers with minimal refactoring.

- Treat AI like a vendor, not air: if access is a single point of failure, it will fail at the worst time.